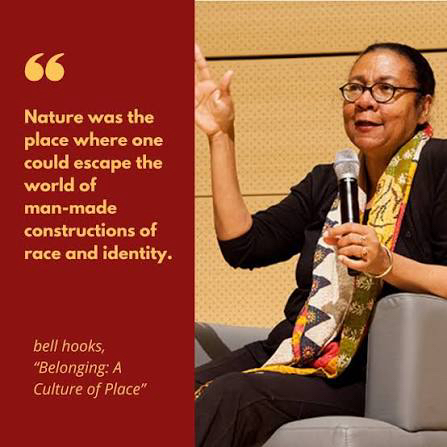

When bell hooks wrote Belonging: A Culture of Place, she framed home as more than a physical location. Belonging, she argued, is an emotional, relational, and spiritual connection to land, people, and memory. It can be a return to the places that shape who we are. Hooks insists that belonging requires honesty about history and community, but also radical acceptance: the courage to love a place enough to tell the truth about it.

Ian Munsick’s newest album, Eaglefeather, released this year, is steeped in the very notion of belonging hooks writes about. Born and raised in Sheridan, Wyoming, Munsick sings not just about the West, he sings from within it. His music is not an outsider’s romantic imagination of mountains and cowboys. It’s the sound of someone rooted, claimed, and shaped by the landscape that raised him. The album opens a window into a form of belonging that mirrors hooks’ central themes: place as identity, place as inheritance, and place as connection.

Belonging is the spirit of place: hooks and the emotional geography of home

Hooks asserted that belonging is forged through relationships with land, community, ancestors, and the stories that live between them. She writes that “the place where we belong is the place where we choose to grow” and that belonging requires both tenderness and truth-telling. For her, rural Kentucky held scars of racial trauma and the grounding of community, family, and memory. Belonging, then, is not simple; it’s layered and lived-in.

She helps us see belonging as a practice: cultivating a deep and emotional tie to one’s origins while navigating the complexity of contradiction.

Wyoming as identity: Ian Munsick’s geography of belonging

Wyoming isn’t just a setting in Munsick’s music — it’s a character, a mentor, a memory keeper. In interviews and songs alike, he credits the land for shaping his worldview: the quiet vastness of Sheridan County, the ranching lifestyle, and the blend of cultures that define the Mountain West.

On Eaglefeather, this sense of place is sharpened and spiritualized. The title itself refers to the golden eagle feather gifted to Munsick by the Crow Nation, an honor that becomes symbolic of how identity and belonging transcend boundaries. The album leans heavily into:

- Ranching culture and family legacy

- The spiritual connection between land and identity

- Intertwined Western and Indigenous histories

- A longing for wide-open spaces even when on the road

Munsick isn’t just representing his home state — he is belonging to it in the way hooks describes: with reverence, clarity, and a sense of inherited responsibility. While hooks and Munsick have very different experiences to the the idea of belonging, the message is clear–place shapes identity.

Place shapes identity: how hooks and Munsick speak the same language

The land as storyteller

Hooks explains that the land holds memory that it teaches, heals, and demands acknowledgment. Munsick mirrors this idea as he leans into the sonic landscape of the West: fiddle-driven melodies, wind-swept arrangements, and writing that feels expansive.

Authenticity over assimilation

Hooks advocates for embracing one’s origins rather than abandoning them to fit dominant narratives. Munsick embodies this in a commercial country landscape often dominated by southern tropes. Instead of adapting to Nashville’s standard, he brings Wyoming with him unapologetically and consistently.

His belonging isn’t performance; it’s identity.

Community and mutuality

Hooks says belonging is rooted in relationships of mutual care. Munsick’s work reveals deep ties to Western communities and ranch families, Native communities, fellow Wyomingites. The Eaglefeather story itself is about being welcomed, honored, and recognized by another culture. This gesture mirrors hooks’s belief that belonging is something we grow with others, not something we own.

Honoring complicated histories

Hooks refuses to romanticize the rural South without confronting its contradictions. Wyoming has its own layered histories — Native displacement, ranching legacies, environmental tension. By centering an eagle feather, a symbol of Indigenous reverence, Munsick steps into a space of acknowledgment. He doesn’t speak for Native communities, but he does honor the relationship.

This aligns powerfully with hooks’s call for ethical belonging.

Belonging as a bridge between cultures: the Western + Indigenous intersection

In Belonging, hooks writes that home becomes richer when we open it to others — when belonging is shared. Munsick’s connection with the Crow Nation suggests a vision of the West that is expansive and relational, not exclusionary.

Where mainstream “country” often erases Indigenous presence, Eaglefeather gestures toward inclusion, respect, and shared place.

This is exactly the kind of cross-cultural belonging hooks calls us to imagine: one rooted in justice, honesty, and connection.

Why this connection matters now

In a moment when identity and conversations about authenticity dominate the cultural space, both hooks and Munsick remind us of something grounding:

We become who we are through place.

To know a person, you have to know their land.

For hooks, Kentucky was both a wound and home.

For Munsick, Wyoming is both vast and intimate — a sanctuary and a responsibility.

Their work together paints a picture of belonging that is:

- Honest

- Rooted

- Cross-cultural

- Relational

- Deeply spiritual

And ultimately, it speaks to something universal — whether you are a Black woman finding home in the hills of Kentucky or a Wyoming ranch kid carrying an eagle feather across the country, the connection and draw of a the land is undeniable.

Leave a comment